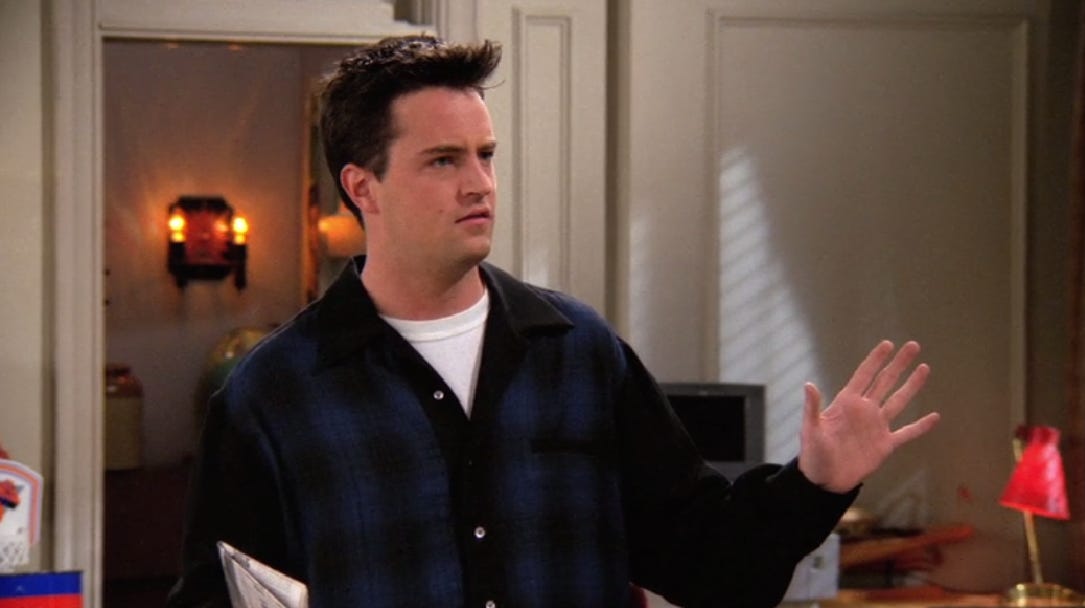

Could this input BE any more comprehensible?

How to activate your mind’s natural ability to pick up languages

In our last issue, we talked about the ‘magic’ formula for first-language acquisition: instinct + input = language acquisition. If you missed that one, we highly recommend taking a moment to go back and have a read, as we’ll be building on the themes and examples that we explored there.

When it comes to second-language acquisition – learning languages beyond our first language (which, we’re assuming, is why you’re here - hi!), what we’re calling instinct may or may not be involved in the same way, but the rest of the formula is the same.

That means input is necessary. And just as a reminder, input is any linguistic data you encounter as you work through the process trying to understand messages in the language.

Remember our child?

“When the child overhears the parents talk to each other, that’s input. When the child’s annoying uncle comes over and tells bad jokes, that’s input. When the TV gets left on within earshot, that’s input too. Some types of input may be more helpful at one stage than another, but it’s all input.”

But, as we also said last time, not all input is created equal. In this issue, we’re going to talk all about what kind of input you need to make your journey to proficiency as smooth and quick as possible.

The science-y bit

One very useful way of thinking of the kind of input that works comes from the scientific literature dating back all the way to the 1970s, when a researcher named Stephen Krashen (watch the video, it’s great!) came up with the concept of comprehensible input.

Comprehensible input is the language you encounter when someone successfully conveys a message to you.

When you’re walking down the street and someone is yelling at you in a language you don’t understand well, you won’t know if they’re saying that you dropped your wallet, trying to sell you something, or warning you there’s a piano about to fall on your head. To you it’s just a string of sounds.

However, if that same person comes up to you on the street and says those same sounds to you, while patiently pointing out the piano about to fall on your head, and you realise that you should get out of the way as a result, you’ve just experienced the beginnings of comprehensible input.

The important thing is that you understand what is said, rather than how it is said. In other words, you get the message, without having to understand the precise details of what words or grammatical constructions were used to convey that message.

Your friendly piano lookout may have used a particular verb tense you hadn’t encountered before, or you may not have even heard the word for “piano” before.

To take an English example, you don’t have to understand the ins and outs of when to use “going to fall” vs “will fall” to understand you need to get out of the way of a falling piano – sharpish.

But there has to be a message! Simply hearing words and phrases out of context does not count. There isn’t any message conveyed by a list of phrases a textbook gives you to memorise, as useful as those phrases may be.

You’re less likely to acquire the grammar behind question formation from reading “where is the bathroom?” in a phrasebook than you are from hearing someone who comes up to you with panic in their eyes and asks you “where is the bathroom?”

It’s the exact same phrase, but this time someone is using it to convey a message to you – to communicate. It’s communication which seems to activate our ability to build up our knowledge of language.

It’s also important that the input contain material slightly beyond your level of proficiency. If it’s too far beyond your level, you won’t be able to understand the message. If it’s exactly at, or below, your level, there won’t be anything new in the input for you to acquire.

Now, these levels aren’t strictly defined. But it’s not hard in practice to tell whether some input is in the “Goldilocks zone”: not too hard, not too easy, but just right!

If you can’t follow the content well, you’ll need to find something easier. If you have no difficulties understanding the content and there’s absolutely nothing new to you (no new vocabulary, no grammatical structures you wouldn’t use yourself), you’ll need to find something more challenging.

In Krashen’s original model, comprehensible input is all you need. Get enough comprehensible input – and you do need a lot – and you’ll inevitably acquire the language. Later researchers have argued with this or that aspect of the theory, but the core of Krashen’s ideas have stood the test of time: comprehensible input is crucial.

What does this mean for us as language learners?

It means our job is to make sure we’re consuming as much comprehensible input as we can.

The trick is that, depending on your level and the language you’re learning, comprehensible input might be hard to find. The lower your level in the language, the fewer things will be comprehensible to you. The more rarely the language is spoken, the fewer things will be available in general – so finding things that count as comprehensible for your level will be more challenging.

Comprehensible input can be hard to find, but at least you’ll know it when you see (or hear) it. We’ll go over more practical tips for finding (or making) comprehensible input, whatever your level, in future issues, but we won’t leave you before giving you a few ideas you can use today:

For some more commonly studied languages, there are graded readers, which are series of books written at different levels of difficulty suitable for different stages of learners.

Media with a visual component, such as comics and TV shows, can be useful sources of comprehensible input because the visuals give more context for what is going on. This added information is like support which you can use to understand higher-level language.

Translations of books you know well in your first language can be good sources of comprehensible input, given that you’re already acquainted with the characters, plot, or topics being discussed.

Probably the best source of comprehensible input is a speaker of your target language who has the patience and knowledge necessary to give you input roughly tuned to your level.

Teachers, tutors, or language exchange partners are a great resource in this regard, in particular if they understand the importance of input in language acquisition. (If they don’t, maybe send them a link to this series!)

That’s all from us for today. Join us next week when we’ll look at an important factor that can accelerate your language learning or hold you back: your own mindset.

Until then, how do you say goodbye in Lingala?

Tikala malamu,

I love the light, humorous, encouraging writing and Krashen's video was fabulous. Not only was the second lesson with Spock clear, I was excited to understand part of the first. Unfortunately, I listened to the video on the way to bed. It was SO engaging!