Why do we keep failing at learning languages?

Or...how you can spend a decade learning a language at school and barely hold a conversation.

Does this sound familiar?

"I took French all through high school but all I can say now is 'Bonjour!'"

To me (Natasha), it most certainly does. I moved to Paris in 2008, ostensibly to learn French “properly”. Whilst I knew I was nowhere near fluent, I got off the Eurostar from London convinced that my 8+ years of school classes and A in GCSE French would give me a great jumping off point. It took only a few hours to realise that I barely had the fundamentals down, and being able to talk (badly) about where I went on holiday would get me nowhere as I learned to navigate the city.

The sad thing is that no one is really shocked by this kind of failure in language learning: but that in itself is weird. Is it reasonable to expect to come out with practically nothing after spending years pursuing a subject in school? Learning languages, actually learning languages, in a classroom just...doesn't tend to happen all that often.

A quick caveat: some classrooms are certainly better than others. And so many language teachers do an admirable job within the constraints of the education system. Here we’re talking about the typical experience of students in the English-speaking world, which isn’t good.

To understand why learning languages in the classroom has such a dismal record, we need first to understand what it means to learn a language.

As a rough definition, to learn a language is to take whatever it is in a native speaker’s head that allows them to speak the language, and to somehow get whatever that is into your head.

The way we go about accomplishing this will be different depending on our idea of what exactly is in a native speaker’s head.

Most classroom learning is predicated on the following idea: what’s in a native speaker’s head is a collection of rules that explain how the language works.

Even from the earliest lessons, you may be taught, in your native language, about the structure of the new language. You’ll be confronted with grammar tables and verb charts, right after you’ve learned to introduce yourself and say where you’re from. Then, in all likelihood, you’ll be taken on a journey through lists of hobbies, colours, articles of clothing, and other things you have no real context for, and little interest in.

This method assumes that knowing language is simply a case of knowing all of the rules that apply to it, like “the second-person plural form of an -er verb is -ez.”

This makes a language seem roughly like any other subject: just like knowing biology happens when you’ve learned a collection of facts describing how life operates, knowing a language would happen when you’ve learned a collection of facts describing how the language operates.

If this is true, you can teach a language like you can teach any other subject: sit students down in a classroom, teach them the facts for a year or so, test them at the end, and voilà, you can say you’ve taught them.

Now, we don’t know if this model is wrong about biology – but it’s definitely wrong about language.

Language is not a subject like biology. A language is not a set of facts to learn.

There are, of course, facts to be learned about a language. It’s true that languages behave in predictable ways that you can describe using rules. If not, linguists would all be out of work. But the curious thing is this: learning grammatical rules doesn't seem to affect how you speak.

This is why we get the A+ student who can't order in a restaurant. This student has been taught using the methods that seem to work well enough for other subjects - they’ve accumulated facts, and can remember them well enough to regurgitate them on-demand for a test. But somehow this doesn’t translate to proficiency with the language.

So…what gives?!

This is a question that many researchers have wondered about. The answer hinges on a proper understanding of what is going on in a native speaker’s head. Once we know what a native speaker of a language has in their head, we can better approach how to help learners attain the same thing.

What’s in a native speaker’s head is an abstract system of unconscious, implicit knowledge about elaborate hierarchical structures that bear very little resemblance to anything you’d actually recognise as a sentence.

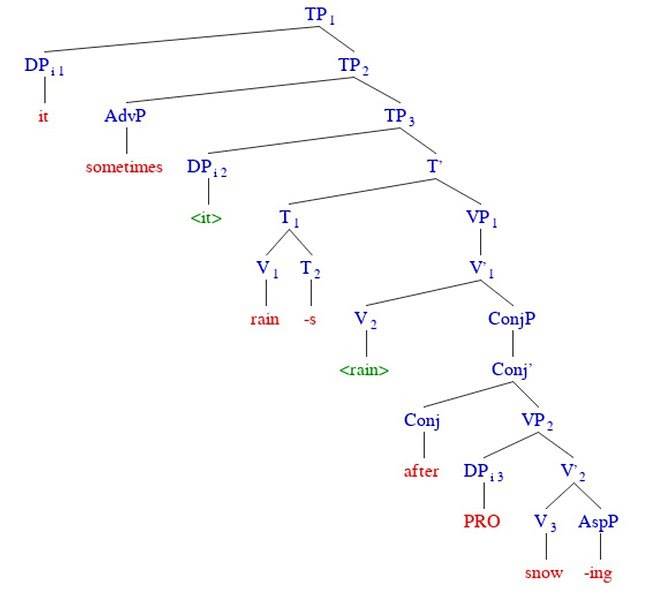

Seriously, you need special software – or a lot of patience in Microsoft Word – to even draw these things in a way that does justice to all their complexity!

Here’s what one of these structures looks like, if you’re curious. If this is frightening, literally do not worry – your mind deals with all of this for you behind the scenes. (If you find this intriguing, on the other hand, you may have a career in linguistics ahead of you.)

This is the sort of thing that linguists get excited about, because the real rules of how language operates occur on the level of these abstract representations. And if you know English, or any other language, for that matter, you’ve obeyed these rules hundreds of times over the past 24 hours.

Here’s an example of something you likely don’t know you know (if you’re a native English speaker).

In English, you can say both: “I seemed to learn Japanese quickly.” and “I tried to learn Japanese quickly.”

You can also say “It seemed that I learned Japanese quickly.”

But you cannot say “It tried that I learned Japanese quickly”.

This is kind of bizarre: the first two sentences appear superficially pretty similar, right? But when you try to change them around a bit to use “It” at the beginning, one works fine and the other sounds so wrong.

Who taught you the difference between seem and try? Nobody. But if you speak English, you know it as well as you know your own name.

Whenever you produce or comprehend language, you’re making use of this abstract kind of knowledge. You know this stuff: you just don’t know you know it.

So if this is what language looks like under the hood, how on earth do you get that into your head?

Fortunately, the human mind has given us a superpower that allows us to build up this richly articulated, unconscious knowledge. You may be wondering if you need to be below a certain age to use this superpower – short answer: probably not. For the long answer, wait for next week’s issue.

The catch is that this superpower only gets activated if the circumstances are right. And, unfortunately, the circumstances are not right in the classroom most of the time.

The reason is that the grammatical rules the textbooks teach us are just the surface facts of the language. They don’t help us build this abstract system at all. In fact, our conscious knowledge of language doesn’t seem to have anything to do with this unconscious knowledge. And imparting conscious knowledge is what the traditional classroom model spends most of the time on. Given this, it’s no wonder the results are so bad.

So, we’ve spent this newsletter kvetching about what doesn’t work. What does? How do we activate our language learning superpower and build our very own abstract system?

Stay tuned, because that is the topic of our next issue.

What were your experiences of language learning at school? We’d love to hear in the comments!

Until then, how do you say goodbye in Mandarin?

Zài jiàn!

Colin & Natasha

Learning a language is very difficult, especially Russian))I really enjoyed learning online at school https://golearnrussian.com/free-russian-lessons/ I passed a free test to determine the level of knowledge of Russian and then I was picked up by a translator, a native speaker. I was very lucky to meet such a qualified teacher. I recommend it.

A good friend who said she's not good at languages asked me last week how I can memorize so much. It was a challenge explaining that I don't memorize words and learning a language isn't about memorizing. Maybe that's why I have so much difficulty with grammar rules.